Familar Faces: My Kin, the Paluchard - The Journal of Anther Strein

The Journal of Anther Strein

Observations from a Travelling Naturalist in a Fantasy World

Written by Lachlan Marnoch

with Illustrations by Nayoung Lee

30th of Lodda, 787 AoC

Sunken River, Clearleaf Plateau

Familiar Faces: My Kin, the Paluchard

I have lacked both the time and the energy to write anything since my last entry. Over the past week we have been engaged in a hard slog to make up for lost time; first through the outer reaches of the Erefal Wood and then descending into the basin of the Veduka Rainforest. As one approaches the rainforest, the erefal trees become gradually stunted. More light filters through from above, and the undergrowth takes proportionate advantage. Smaller trees become more common - eucalypts, palms, and raintrees - until eventually, the erefals give way entirely to lush jungle. As I hoped we would, we came to a series of old game trails sloughed by other Paluchard. Still, it has not been easy going.

The journey has been made infinitely more pleasant, however – at least for me – by the abundance of life and being that now buzzes all about us. Birds of every sort call from the trees, frogs croak from the undergrowth, pythons slither away as we approach. Tarantulas prowl the path along with us, and webs built by other spiders glisten between the trees. Ants of every conceivable size teem in little marching lines, holding assorted burdens aloft. The monotones of the Erefal Wood have been replaced with vibrant greens of every shade, and flowers of many other hues beside. It all reminds me so very dearly of my time as a child, watching bees and daydreaming about joining the Disciples of Sunon. Little has changed, except that I am now much better equipped for such observations. I feel more alive than ever. The familiar edible plants of the rainforest even allowed me, yesterday, to eat my first vegetarian meal in some time. This was quite a relief.

Our difficult work has paid off, bringing us at last upon the Sunken River. We reached its bank yesterday afternoon and took a celebratory early mark from walking. I intended to use this extra time to write, but after setting up camp I could do little more than collapse. Today, after a healthy sleep-in, we set off down-river.

We had been on our way for a few scarce hours before coming across a pair of my kind, swimming for fish in the river – one male and one female. I noticed their sleek backs instantly, arcing downward in twin dives, with spears gripped in their tails. I knew that once we were in the Rainforest we couldn’t fail to happen across Paluchard in the rivers – the place is replete with them.

I hailed the fisher-people from our bank, and they swam across to us right away. Although there were a few queer looks directed at Prentis, the pair seems friendly enough. Our languages are not mutually intelligible, but have enough overlap in vocabulary for us to communicate in a slow, broken fashion. For a Swampland krona1 each, they were only too happy to carry us downstream to their village.

Before leaving, I joined them in the water (through which my species can see quite well), and watched as they engaged in their hunt. I gathered that they were stalking a lesser marsh serpent concealed among the reeds. This would have been a significant catch, had they managed it, but it escaped - which should come as little surprise to those familiar with the species2. The fisher-people seemed to regard this failure with cheer, and had already made up for it by spearing a small pile of other fish. We waited for them to load the last of their haul - mostly large piranhas, with a couple of cod and a single river barramundi (Blas iomchaidh) - before boarding together. The fisher-people grumbled only a little, and in apparent good humour, about the sacrificed space. It is from the stern of this boat that I am now writing, while Prentis sits at the bow; they would not allow either of us to contribute to the rowing, I presume as a hospitality. The way our species is constructed, rowing is by necessity a two-person task - unless one enjoys spinning in circles.

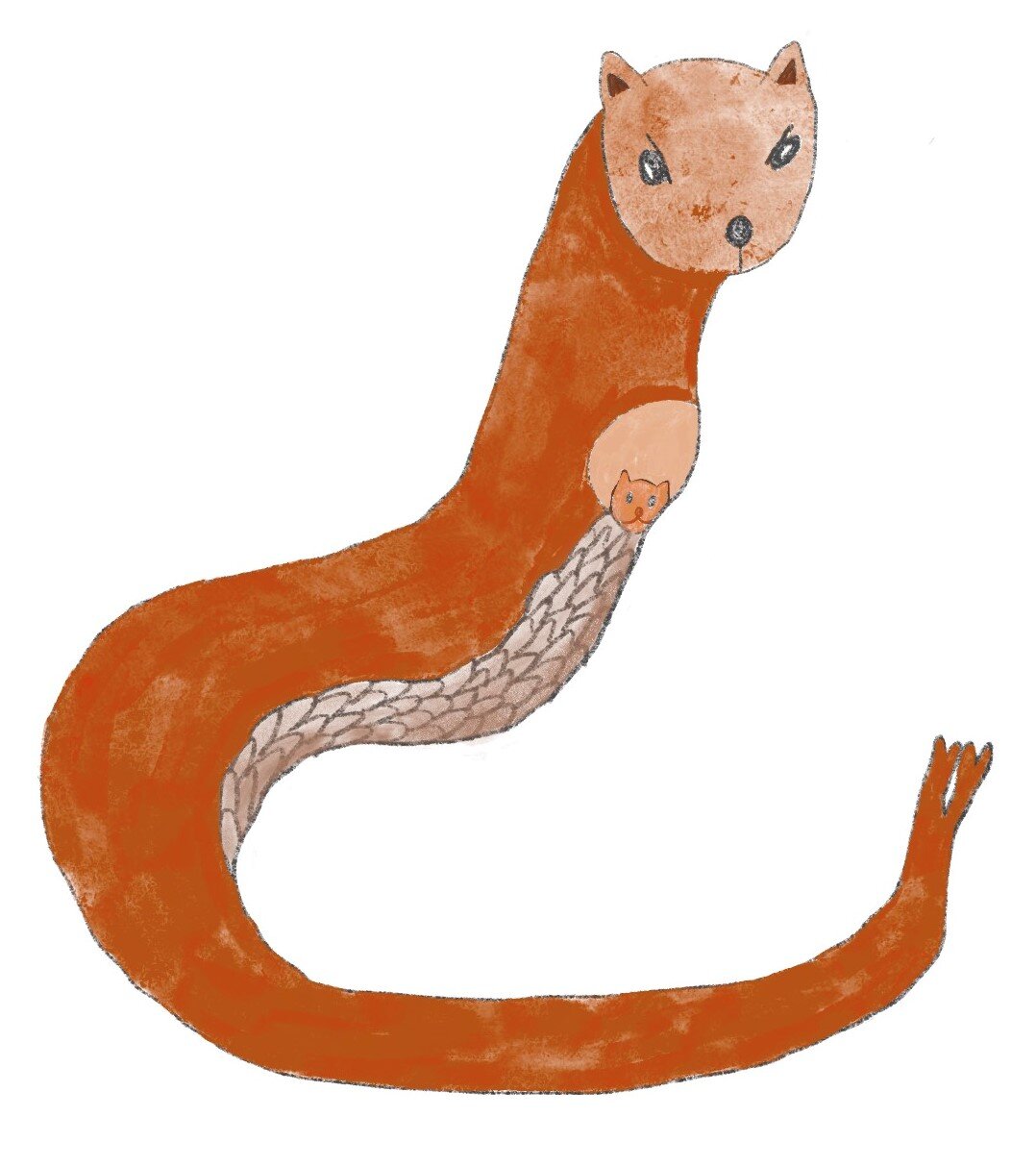

My species, the Paluchard (Venator lustrum), are legless mammals, belonging to the order Baemata – informally, the ‘marsupial serpents’, which include the splitters3 (family Razofidae) and twisters (family Begoniaxidae). Other members of Baemata can be found sunning themselves along the northern shores of Proesus, or slithering across the inland deserts. Atop a long body, which indeed resembles that of a snake in form, is a squat head with round ears and a short, whiskered snout, tipped with a black nose and filled with an omnivorous variety of teeth.

Although we lack true arms or legs, Paluchard tails terminate in two pairs of multijointed pseudo-fingers - the very digits with which I am holding my pen to write these words. As the spine is very flexible, we can curl over on ourselves to bring these fingers to wherever they are needed. The tail itself is deft and strong, and can be wrapped around objects for lifting and coarse manipulation. This is demonstrated in the paddling technique of our two escorts – the tail encircles the oars part-way down while the digits grip the handle at the top. When held together, which is the position to which the digits default when relaxed, they are almost indistinguishable from the rest of the tail.

Other splitters have similar digits, termed graspers, although none are so capable as ours. Especially in those splitters with an exclusively aquatic lifestyle, the fingers are used during underwater mating to clasp the sex organs4 of the pair together5. They are missing entirely from the twisters, which are truly limbless.

Paluchard are very comfortable in the water, and especially in the many rivers of the rainforest. My kind are excellent swimmers, rivalled among the sapient species only by the Maragana. However, traversal by boat remains considerably faster, and much less exhausting. Our fur is sleek and waterproof, to accommodate our semiaquatic lifestyle, and varies in colouration from black to light tan – a feature which correlates with, and has been used to classify, race. The fur of our escorts is a handsome brown. My fur is dark auburn, unusual but not unheard of in my home region. I’ve always rather liked it, although it has drawn unwanted attention at times.

I was thoroughly startled just now by the emergence, from the pouch of our female escort, of the head of a Paluchard child. I had somehow failed to notice the significant bulge on his mother's torso. In the Swamplands, my home country, such a thing would not be allowed – the mother and child would stay at home while the father engaged in the fishing. Perhaps these far reaches of the Rainforest are more flexible in their gender roles. I applaud it.

The mother laughed at my surprise. She allowed the child to slither down into the boat, where he spoke to me in babbled fragments of his parents’ tongue. Despite his utter charm, he was even harder to understand than his parents, and I could only respond with nods and the occasional “is that so”.

The child quickly lost patience with this and moved on to Prentis – whom he regarded with complete fascination. Prentis’ ability to communicate with the little fellow was even more diminished than mine, but he seemed to make up for it with sheer novelty. The child chittered with laughter at the Austium’s various noises and even engaged in a wrestling match with his forelimb. The mother watched these interactions warily but did nothing to prevent them. I admire her for this – few are the Paluchard in my hometown who would abide an Austium in the same village, let alone making physical contact with their children.

After a thorough inspection of his parents’ catch, the child climbed back into his mother’s pouch, head poking out to watch us. She began singing, joined in beautiful harmony by her partner. Although the words and tune of the song were unfamiliar, its intent was not, and I found myself filled with a wonderful pained longing - for the warm comfort of my mother’s pouch and the innocence of childhood. Paluchard mothers usually talk and sing to their babies before their ears have even developed, establishing a powerful bond that resonates well into adulthood (and occasionally, it seems, stimulates whatever part of the brain is responsible for nostalgia). The child was lulled quickly to sleep.

Most marsupials have their birth canals proximal to their pouches, a sensible measure in the interest of the newborn joeys forced to embark from one to the other. This is not so for our order6 – instead, the pouch is found not far down the body from the head, while the birth canal is near (or on, depending on how you classify it) the tail. After giving birth, the new mother reaches around with her tail and uses her digits to deposit the tiny, hairless infant in her pouch. Located on the underbelly, the pouch points downward from the head and can be held tightly closed with sphincter muscles, so that it is almost waterproof. The child can breathe air channelled to the pouch from the lungs, via an extra trachea that opens and closes reflexively. Before they are old enough to slither, we7 carry the young in the pouch at all times; and often after that, until the child outgrows the pouch. I recall throwing a great tantrum on the day of my permanent eviction from my mother's - although my weight and wriggling must have been causing her considerable discomfort by then. The pouch also comes in handy for carrying small items – especially those that should be kept dry, such as pocket journals. One should be careful what one keeps in there, however, for the pouch is somewhat susceptible to infection. I write only from experience.

The method with which my species moves, along with our relatives the twisters and splitters, is best compared to that of snakes. We use lateral undulation – better known as ‘slithering’, the twisting of our bodies from left to right – to propel ourselves both on land and in the water. Such a mode of travel is totally unknown in the mammals beyond Baemata, whose spines can only bend forwards and backwards to any great extent. Even the ancient whales – who it seems went to huge lengths in distinguishing themselves from other mammals - only bent up and down, whereas all other known animals with fish-like forms swivel from left to right as we do.

A Paluchard’s underbelly is covered with broad keratin scales, as one finds on a pangolin, instead of fur. This feature is missing from the true aquatic splitters, but is found in a number of our amphibious and terrestrial relatives. The scales come up to just beneath the pouch entrance. They make our method of locomotion possible, smoothing friction with the ground. Despite our leglessness, Paluchard are also quite accomplished tree-climbers. Paluchard peasants often live in treehouses, preferring this to the swampy ground of the rainforest.

Wildlife often balks at the sight of my species, especially if it is not allowed to scent us first. I suspect this is because, at a distance, it is easy to mistake us for very large snakes. This is especially so within Veduka, where we share a range with several pythons comparable to or greater in size. It is a sensible response in any case, for we are prolific hunters.

Unlike snakes, and unlike the twisters, we of the splitter family can carry the forward quarter of our bodies completely upright when moving – snakes are capable, of course, of raising themselves into a striking position, but not while in motion. This ability is a necessity, for otherwise our young would be crushed8.

I will state here one tantalising fact concerning Paluchard physiology: that the skeleton, although invisible from the outside, includes the rudimentary and unused bones of a pair of forelimbs. They have the same basic structure as all tetrapod limbs – ulna, humerus, radius and the rest – but much reduced in scale. The bones lurk embedded in the muscle of the torso, quite separate from the rest of the skeleton, and can be located, with some prodding, from the outside9. In newborn babies, these ‘limbs’ actually protrude as a pair of comical stumps, in precisely the location of the forelimbs of other marsupial joeys (such as the wobali, the vaga and the gambuk), before being absorbed into the growth of the body.

I have often wondered what utility these small bones can have. The answer, it seems, is none – they play no apparent role in locomotion or any other faculty. The term "vestigial", coined lately by naturalists in Manifold, springs to mind, although one must be careful where it is applied – for its implications are vast. A vestige is something left over, a remnant. For a thing to be left over, there must have been something to precede it. Use of this word implies a shift, a change, in the use of the limbs, that they had some prior function but that this changed or was lost over time. However, I am becoming more comfortable in the term. After all, what explanation is there for the existence of these useless bones, other than as remnants of the limbs of a past legged ancestor?

In addition to this one fact, I must here indulge on some further speculation, for a related issue of equal interest has sprung to mind. One might contemplate on such a relationship of descent existing between the rear limbs of a land marsupial and the tail-digits of the Paluchard, the internal structure of which also matches the limbs of other tetrapods (if somewhat abbreviated). My mind often travels on such fancies. As the rear legs of the marsupial were no longer used for walking, perhaps they deteriorated into mere digits, finding another purpose in aiding reproduction – then, as my kind found a new use for the digits, they re-specialised into the dextrous pseudofingers we are equipped with today. Fancies only, I’m afraid, until the time can be taken to properly analyse such things. I’m not yet ready to delve into the role of use and disuse in the development of traits, but I certainly have some ideas.

Paluchard have a massive majority here in the feudal states of Veduka, and a slim one in Baaikhan, Northtine, and a handful of other nations. We can be found as a minority in almost every other country in Proesus. Although we generally prefer warmer climes, my species lives as far south as the fringes of the Circle of Frost10.

Even so, the history of my species is tied to the Rainforest. We have existed here for as far back as evidence can be made to tell, and were likely born here11. Naturally, though, other civilized species exist here in minority. Although my species dominates the numbers and the politics here by a wide margin, there are settlements of Austium, Nuntium and even Essilor scattered throughout.

These non-Paluchard inhabitants are rarely granted any rights beyond freedom from slavery, and this not always. Their lessened privileges mean that many depart the Rainforest when freed (particularly Essilor, who find the humidity most unsettling). However, some choose to stay, either integrating into Paluchard society in some fashion or forming settlements of their own. Brave souls indeed - my race has never been famous for its hospitality to other species (which has made this pair’s tolerance of Prentis all the more surprising), even those it has itself abducted. I suspect more than one of these settlements has, over the centuries, disappeared quietly at the convenience of the local feudal lord.

The region has a long history of slavery. Austia and Essilor, in particular, have been the more popular victims. Austia are valued for their skill at coaxing plant life to grow, and have frequently been enslaved as farmers of bogvine. Essilor, although ill-suited to the swamps and thick undergrowth of my homeland, are readily available in great numbers just south of the Paluchard Kingdoms. They are often captured and sold northward by the slave trade in Fringe. These practices are gradually disappearing, having been outlawed in some half of the Kingdoms, and pressure on the other half is eroding them bit by bit (pushed, partially, by the Order). I doubt, however, that I will live to see them abolished entirely.

The Veduka Rainforest forms the core of the Paluchard Kingdoms. Several of these monarchies are centred on major tributaries of the Veduka River, the lifeblood of the forest. Sadly, many of my kind still live in a system of feudal allegiances here, most notably in the Swamplands - the original seat of our power. I was born in the Swamplands, but am held exempt from the laws of serfdom because of my service with the Order, which most of my people greatly esteem. I can only count my luck.

Although the system varies slightly between kingdoms, there is generally a single ruler at the head of the nation, usually a king (although queens have ruled on rare occasion). This nation is divided into smaller fiefdoms, each ruled by some manner of lord owing allegiance to the king. The people living in the lord’s fief are considered his subjects – in past centuries, this has included the right to do with them as he pleases. In several kingdoms, the subdivisions are nested even deeper, with the fiefs divided into counties or duchies, and each ruled by a correspondingly lesser lord. The most egregious such system is in Torvus, where it has been flippantly claimed the subdivisions repeat infinitesimally. Political philosopher Calypse Altern wrote, of Torvus: “even a peasant is given domain over the piranhas in his river; the piranha, who must pay tax to the peasant, extracts it from the water flea. The subjects of the water-flea are as yet unknown to science; we are able only to infer that it is with great cruelty they treat the lesser microbes owing them allegiance.”

He exaggerates, but not a great deal.

Recent decades of class struggle have brought incremental improvement on the indentured servitude of the past. But it goes not nearly far enough, or in enough places. It also does little good for the non-Paluchard slaves. Paluchard nations in other regions are said to be more liberal, perhaps through the moderating influence of other species. Baaikhan, the other major stronghold of our kind, even employs a representational form of government known as “democracy”. However, whether cultural or inherited, there certainly seems to be an authoritarian bent to many of the systems created by my species. I suspect some of the Order’s obsession with rank and hierarchy might have been inherited from my people, as the Order of Febregon’s historic origin lies right here in the Rainforest.

I have also long suspected that the Order’s rigid rejection of female clergy (along with its other diverse discriminations related to sex) has descended from my species’ tendency toward misogyny - a disease particularly rife in the rainforest kingdoms. An unfortunate feature of Paluchard society is its general dominance by males, and the lessened power and rights of females by comparison. Females are considered, by most Paluchard, inferior in many ways - intelligence among them (a notion for which I have seen no convincing evidence - but then, I would say that). Although this bias is by no means unique to our kind, it seems more pronounced than in any other sapient species. Exceptions exist, of course, such as in the Queendom of Gogiri, where the monarchy is traditionally led by a female. But even here persists a general assumption of the female’s “lesser” nature, to which the Queen is considered a divinely-inspired exception. The existence of a female monarch there has caused no shortage of historic tensions with the Order.

This bias, in turn, I have lately thought might be linked to the pronounced sexual dimorphism of my kind. The physical differences in our species are readily apparent while watching our two escorts, sitting next to each other, exerting themselves for our transport. The male is longer and of significantly greater musculature, while the more slender female, of course, has a pouch12.

This has leant itself to a division of labour unfortunately reinforced by nature – the feeding and care of the family are left to the mothers, while the fathers engage in hunting and other physical activities13.

A behavioural dimorphism such as this exists in most marsupials, and many other mammals – but I cannot help but feel that such traits, even those apparently written in our “nature”, can and should be overcome in the name of justice. I think that from assumptions about gender roles based on these physical differences has ultimately sprung the entire repressive infrastructure of the Paluchard patriarchy. We no longer live according to nature’s whims – like all intelligent races, we have set ourselves apart, found methods of survival that leave the "natural" ways behind. Why not leave this behaviour behind too? Just because one thing has always been done is no reason to continue it. But then, what would I know. I’m just a female.

We make camp now with our escorts. If I understand correctly, their village is only a few hours further downstream; they expect to reach it before midday tomorrow. There we shall bargain for a boat of our own. Although Prentis and I tried to eat only from our own supplies, our companions insisted on sharing some river barramundi with us – cooked to perfection atop a blazing fire. I didn’t have the language or the heart to explain my vegetarianism, and so, the fish already being caught and killed, I allowed myself one last violation. If their behaviour is any indication, we can expect a most hospitable welcome at their village tomorrow.

1 Not that this currency is much good out here, most of the time – but I expect enough inter-Kingdom merchants make their way even to these backwaters for the coin to be of some value at some juncture.

2 Actually a type of very large eel, the lesser marsh serpent (Minus samus) is lesser only in comparison to its cousin Soldeenus rubinus, the greater marsh serpent. The lesser species has a reputation for wile and cunning, and often steals from the nets of Paluchard fisher-people. It may have been such a theft that provoked the pursuit of this specimen.

3 I feel comfortable including the Paluchard in this family, as we share all the characteristics that matter; however, it should be noted that many naturalists are reluctant to classify any sapient species among the mundane phyla, preferring to hold them separate. This runs, in my view, totally counter to observable facts. If I should here refer to my species as distinct from the splitters, it is only from the long indoctrination of convention.

4 Found not far from the fingers, they are usually internal but extend when called for.

5 We use our digits that way too, although I personally prefer to have my sex on dry land.

6 Our lack of distinct limbs would make this very challenging, at any distance. Although older children like the one described here have little trouble scaling their mothers, a hairless newborn lacks the coordination and coefficient of friction to perform such manoeuvres.

7 I used the collective pronoun here unconsciously, despite never having undergone this process myself. Not my cup of tea, this child-rearing thing, but, with heads far too big for their bodies, I do find them irresistibly cute - once they’ve grown their fur, that is. I usually regard the pink, black-eyed, alien things that first emerge with a faint revulsion. It would not do, of course, to say so in the presence of a Paluchard mother.

8 Twisters have found an alternate means of sheltering their young – the pouch is covered by large keratin scales, forming a stiff shell with an interior hollow. The trade-off is in the pouch’s flexibility – it cannot expand much to accommodate the joey’s growth, and he is therefore exiled at an earlier age.

9 I often probe absentmindedly at my own while lost in idle thought, a habit that has earned its share of strange looks.

10 Each of the civilized species has colonised environs very far removed from their climate of origin - such is the wonder of sapient technology.

11 The Book of Dreams, specifically the Dream of the Origin, states so explicitly.

12 Both the supple form of the female and the bulging muscles of the male have a good deal of aesthetic, even sensual, appeal, especially when placed on display in this manner, and particularly for one starved of conspecific contact for so long. Mind on other things, Anther, mind on other things.

13 A male author might here say “hard labour” instead; such an author would not have any understanding of just how much labour is involved in raising children, and should probably try it himself.