Blackweed, the Floor of the Forest and the Way Ahead - The Journal of Anther Strein

The Journal of Anther Strein

Observations from a Travelling Naturalist in a Fantasy World

Written by Lachlan Marnoch

with Illustrations by Nayoung Lee

20th of Lodda, 787 AoC

Erefal Wood

Blackweed, the Floor of the Forest and the Way Ahead

This morning, Prentis and I followed the walkways to the limits of Leafshrine’s influence. We were escorted by what seemed like the entire population of the village – a much grander send-off than Taragos received. Requit’s parents watched while I played with the little Austium one last time, feeding her a crumb from my supplies. She chewed and watched me with eyes and antennae as Prentis and I waved farewell. I know she does not yet understand what is happening. Perhaps she will remember me.

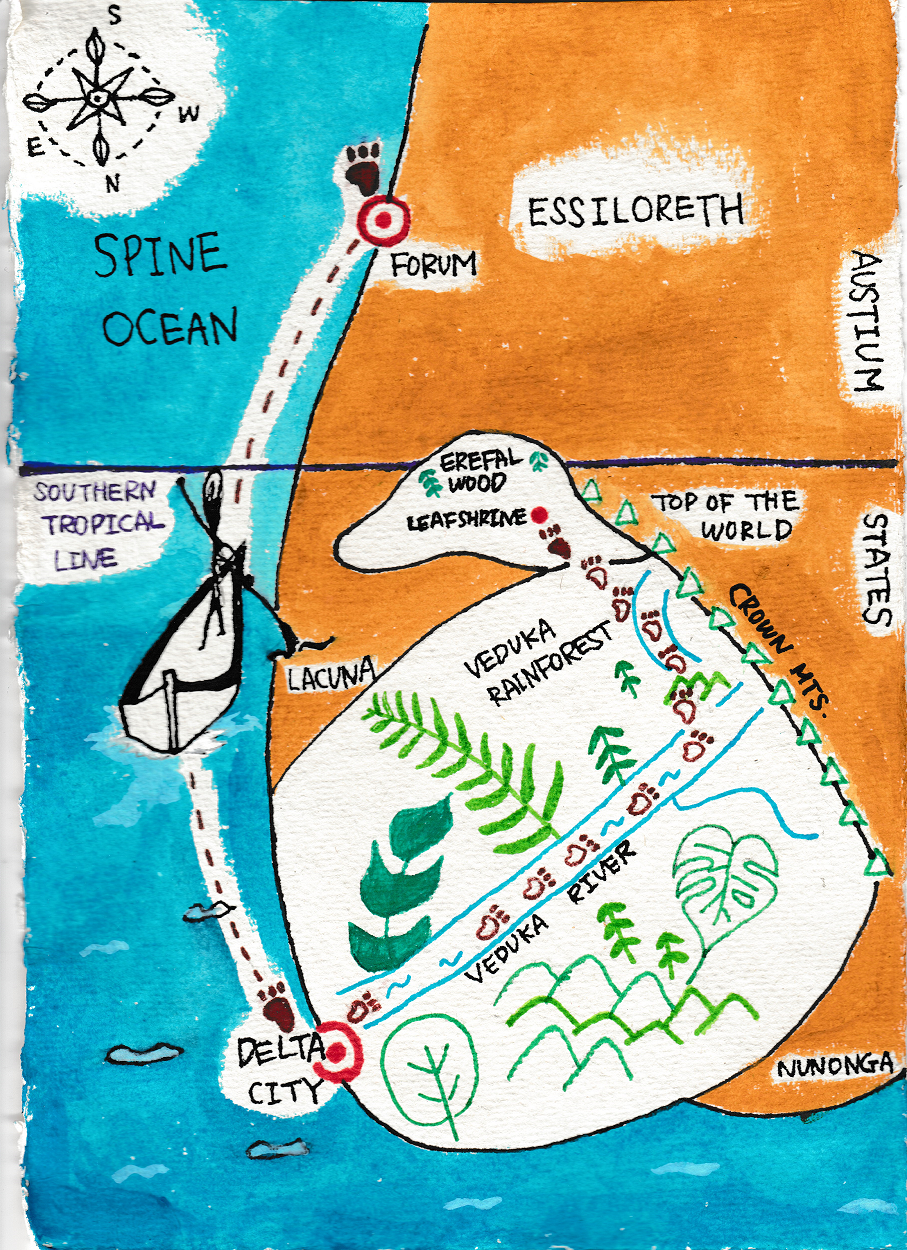

After a hard day’s hike along an old, disused path, the two of us have made camp in the lowest branches of a young erefal specimen. The immense detritus of the trees is strewn about the forest floor, so progress is slow; but progress it is. Having planned our route properly last night, we are making our way north-west. Although we are moving in the opposite direction to our ultimate destination, there is a method to our movements. I will attempt to draw a brief map here to demonstrate our course. I am by no means a skilled cartographer, but here is my understanding of the shape of the world - or, at least, the small portion of which we are soon to cross.

I make no claims as to the accuracy of the coastlines, which are a good deal more rugged than my penmanship is apt to portray. Caring little for borders, I not attempted to draw them on here; I also cannot find it within myself to attempt replication of the patchwork of monarchies present in the Veduka. I do, on the other hand, quite enjoy drawing these little triangles to represent mountain ranges, although the position of the peaks is by no means accurate. During the more artistic intervals of my childhood cartography phase, I even endeavoured to cover my forests with individual trees. I no longer have the patience for this process. Our continent has always struck me as resembling a great starfish in motion, of which the Essichard subcontinent1 is the north-eastern arm. This map covers the northern portion of Essichard, roughly two-thirds.

Here I have marked our planned route across the subcontinent. We hope to procure a boat and to follow the Sunken River until it joins the Veduka. On this, the greatest river in Proesus, we will enjoy a leisurely row all the way to Delta City. From there it should not be difficult to find passage by sea to Forum. A circuitous route, to be sure, but possibly faster than proceeding across Essiloreth by foot and belly. A good deal more scenic, too. As spectacular as the trees of Erefal are, they do become a trifle monotonous. Autumn is beautiful, in my opinion, chiefly because it passes, and can thus enjoy comparison to the other seasons. The vibrant greenery of Veduka will be a welcome change. We will also be able to observe the animals and plants of the Veduka Rainforest, which were among my greatest childhood joys. This will be my first return to the Rainforest since I left for the College of Forum, some fourteen years ago, and I look forward to finally applying my formal skills to the wildlife that inspired me to study the living sciences in the first place. Prentis has never visited the Rainforest and is quite content to join me. Neither of us seems in any great rush to return to Forum.

We have just made a dinner of some of the cured meat gifted to us by the villagers. I am normally a vegetarian, but I have needed to suppress these habits on my mission here - the people of Leafshrine look on them most unkindly. Their worship of the plant kingdom leads them to a belief that the eating (or, indeed, any use that entails the harm) of a plant is a grave sin. They are hence strident carnivores and fungivores2, going to great length to avoid any leafy matter in their diets. As Austia can remain perfectly healthy on meat alone, we did not endeavour to change this3. Nor, I think, would we have succeeded, and the resulting hostility of the village would have become quite unmanageable.

Prior to our arrival, hunting was the villagers' only means of acquiring meat; despite their apparent skill at it, this was causing a slow and painful slide into famine. After our ministrations, they keep a breeding stock of ovices, which they use for both meat and eggs, as well as a variety of insects bred for the same purpose. They still hunt nolaegi and skath on the forest floor, for which they kept grubdogs even before our arrival. Occasionally they might even take rowax prey, although this I did my best to discourage. The Leafshriners’ meat-heavy diet, combined with their moratorium against fire, made life quite difficult for the mission at times. Austia may eat uncooked meat without difficulty, but the stomachs of Paluchard and Essilor are somewhat more delicate. Taragos managed to procure a magical4 flameless stove before leaving Forum, intending, I am sure, to keep it for himself; he begrudgingly allowed the rest of the mission to make use of it once our circumstances became clear. On no single occasion did he fail to complain about it.

I would dearly appreciate the use of this stove now; we decided to forego a fire tonight as well, having come today upon a pile of dried rowax droppings by the path. Judging from the age of the dung, the great beast might have left the area, but there is no saying for sure. Although our preserved meat is perfectly edible, it would benefit greatly from a stewing. I look forward to returning to my preferred subsistence, but it may have to wait until we enter the Veduka – the wild plant-life here is not of the most edible sort. For tonight we have augmented our ovix5-meat with a few wild mushrooms, found growing on the detritus of the forest floor. Although vibrantly yellow, normally an indicator of a poisonous specimen, this is a trick. This species is quite edible, and only mimics its truly toxic relative, Signum aleam. Identical to a brief glance, the mimic is betrayed by a sprinkling of tiny red dots within the underside of its cap. The Leafshriners taught us the trick of distinguishing them. I shall have to check the archives, but I believe the edible variety to be undescribed; as far as I know, no naturalist has previously discovered the difference between them. I have preserved a sample in my pack. Perhaps I shall even get to name it! A fine chance that would be – perhaps Signum falsum would be appropriate if they prove to share a genus. Or, in honour of the true discoverers of the fungus, Signum leafshrinus.

Pondering the relationships between the two mushrooms, and their potential animal predators, raises many questions. How is it that animals come to recognise the signalling, and to avoid the mushrooms? It cannot be from personal experience, for those having directly encountered the poison rarely survive. It must be an instinctive understanding, at least in those species that do not learn from their parents; but how does this instinct come about? The advantage offered by the pretender’s mimicry is obvious, enjoying the same protections as its cousin without expending the effort required to produce toxins. But how does it come by this advantage? Such questions form the core of the investigations I wish soon to embark upon.

There is no grass to be found on the forest floor, and few living plants of any kind. The exception to this is blackweed (Laqueum viris), which is unusually common here. Owing to this, and the shortage of other foodstuffs, travellers in these woods might be tempted to augment their meals with a few blackweed leaves. One should resist this impulse. Appearing, at first, as nothing more than a circular clump of long, curled, vine-like leaves, blackweed is actually a most fascinating plant.

It is coloured, as the name suggests, a shade of green so dark as to appear black, making it difficult to spot in the shadows of the other plants it prefers to shelter in. Although unremarkable to look at, blackweed is carnivorous. There are numerous other examples of plants which sustain themselves partially on animal meat; pitchers and vases abound in Veduka, while sundews, stardews and waterwheels are found throughout Proesus. There is even, if reports are to be believed, the wraproot tree of the Old World. Although a most un-plant-like habit, it is also not unheard of for such plants to move rapidly in response to external stimuli; the sundew curls its tentacular leaf around the insect unfortunate enough to take berth on it, while the leaves of the flytrap and waterwheel can be mistaken for mouths from the fashion in which they close around their prey. However, no other common plant is quite so voracious or as aggressive in its predations as the blackweed.

When triggered by the action of an insect in its vicinity, any of the plant's numerous vines will shoot swiftly toward the unfortunate animal. If successful in meeting it, they then wrap around the body. The speed and unerring precision with which these graspers are launched can be startling. A dose of venom is then delivered into the prey with a set of thorn-like protrusions. Once the prey is subdued, the vines retract once again, keeping a firm grip on their prize. Paralysed or dead, the unfortunate creature is deposited in a central chamber, similar in function to the maw of a pitcher plant. Water laced with digestive chemicals is present there to slowly dissolve the animal.

The length of the blackweed’s vines is deceptive, as they curl upon themselves when inactive. When triggered they may extend to several times the apparent radius of the plant. The mechanism with which it performs its acrobatics is a mystery, despite intense study. The plant’s means of sensing its prey is believed to be linked to the delicate hairs adorning its vines, perhaps able to detect vibrations or micro-changes in air density. The plant attacks and consumes any invertebrate up to a certain size, proportionate to the size of the plant itself. An animal of more substance than the plant can handle will not trigger a response. How the plant can discern the size of its prey, I do not know; perhaps it is linked to the magnitude of the signals it receives from its hairs. It can be tricked by slight movements of a single limb, but only after standing very still for some time 6.

Blackweed is the only known example of a truly venomous plant7. Many others are toxic when eaten, and many more deploy spines, thorns or prickles in their defence; but blackweed is the only plant known to combine the two, using thorns to inject venom in the same manner as the fangs of a spider. The venom is only released if the grasping action is triggered; one is not envenomated by brushing against the plant (although the thorns might still tear at the flesh). The venom is, unusually, toxic on both consumption and injection, and is present throughout the leaves in their entirety. One should therefore not eat the plant, for even thoroughly cooked leaves can cause illness and death. The scent the plant emits is certainly an appealing one, no doubt a tactic for luring prey.

I am reminded by the plant of the Leafshriners, who grow blackweed in great clumps on the forest floor below their village – especially, now that I think about it, in the vicinity of their revered central erefal. I could see this being used as a method of catching food, should they seize the blackweed’s prey before it was fully digested, but they never tried this – I doubt they would ever deign to deprive a plant of its meal. The plant serves a different purpose. The Leafshriners know the art of extracting and distilling the blackweed’s poison, all without any apparent harm to the plant. It is with this that they hunt, dipping spears and arrows in the viscous concoction. Although this specific practice is, so far as I know, unique to Leafshrine, cultivation of the plant is not uncommon.

Its numbers have risen in recent decades, having been introduced by sapient activities to regions where it was previously unknown. A particularly hardy plant, it is now found in all regions of the continent apart from the Ractanos Desert. Although considered an invasive weed by some, it does little harm surrounding plant-life. In fact, there is some evidence that it encourages the growth of the surrounding vegetation. An effective fertiliser can, indeed, be made from its ground-up remains. Some of the more enterprising farmers across Proesus cultivate blackweed both or fertiliser production and as a pest control method - eliminating nuisance insects.

I do not know the purpose of the blackweed's habit of aiding other plants - what could blackweed gain by promoting its own competition? Perhaps the key to this mystery is related to its carnivory. By taking live prey, much of which prefers an overgrown habitat, the blackweed might compensate for denied nutrients. It could be a more general example of the kind of commensal relationship one observes between certain other species of animal and plant, in which both individuals benefit. Such things are usually limited to a pair of species, but I see no reason this general philanthropy for plantlife (philherbropy?) might not exist should it result in profit for the benefactor.

Despite being apparently native to Proesus, the spread of blackweed is cause for concern. Although insects are considered of secondary importance at best, and at worse an outright nuisance, I believe they are much more fundamental to the living systems of our world than most will acknowledge. Rare or vulnerable insect species might be harmed by a rise in blackweed numbers; if an insect species were to disappear, the impact on the animals that feed on it or the plants that rely on it for pollination would be severe.

The scant records of blackweed surviving from the Age of the Limbless, it is interesting to note, do not mention it consuming anything larger than a fly. It may now readily be observed snatching invertebrates of quite a substantial size, such as large spiders and beetles. I have even seen larger plants snatching small birds from the air. Whether this is simply an omission or incompleteness in the records or a genuine change in habit is difficult to discern. But if the range of prey the plant can take is indeed increasing, the potential ecological8 impact must be proportionately greater. We may be inadvertently sowing the seeds for future disaster.

To draw attention to the minimal plantlife at ground level is not to say that the floor is bare, or of easy passage – the discarded wreckage of the erefal trees makes for a great deal of clutter. It is upon this detritus that the beings of the floor found their existence. The erefal trees are doubtless core to the ecosystem here. The forest floor teems with animals, plants and fungi that feed on their detritus, and animals (and plants) that feed on them in turn. Woodlice, millipedes, termites9, and a host of other invertebrates eat the rotting wood and leaves, and what is left makes its way to the abundant earthworms in the soil. Fungi and lichens grow on dropped branches and are harvested by colonies of farming ants10. The Essichard echidna (Satallus essichardus) can be found eating the ants and the termites. A variety of small mammals and reptiles live in burrows between the erefal roots, sheltering from the grubdogs (Vermis canis) and other predators that patrol the floor. The vast millipedes known as nolaegi (Nolaegi hwangje) eat fallen leaves, and sometimes scale the trunks in search of fresh ones.

The upper reaches of the forest are a different story entirely, the canopy being thick enough and distinct enough in the wildlife it supports to be described as a separate biome. Many animals live there, many never venturing to the floor. These include the canopy maimou (Conopeo altas) and the erefal parrot (Laetus erefalus), known mainly from the broken cadavers that reach the forest floor. There seem to be other parasitic or commensal plants to be found there, where the suns can reach them, in addition to the giant’s leghair – rare is the parrot or maimou that can survive on leaves alone. I have collected some samples of thoroughly-smashed fruit that must have fallen from on high, and the rowax droppings contained similar seeds.

No plant beside the erefal attains any great height here, but a number of shrubs and bushes scrape a desperate living from the little light that filters through to the floor. There is no doubt, now, that plants sustain themselves on sunlight, at least partially. People have known this since ancient times - one can hardly miss the manner in which a flower turns its face toward Sororius, or the way the bogvine worms its way toward a patch of sunlight; or the fact that a plant kept in the dark, even if allowed ample access to water, air, and fertiliser, will soon wither and die. Recently, though, magical techniques have confirmed this notion. Biomancers can now trace the energy of the sunlight as it is captured and stored by the leaves of the plant. Alchemists have yet to isolate the precise chemicals responsible - an intact plant is required for the process to continue, and alchemist usually require their subjects ground to a pulp - but my money would be on whatever it is that turns plants green. The energy is shown to enter mostly in the leaves, but also, to a lesser degree, wherever the plant is verdant. Plants are also known to take in ‘bad air’ and release respirarium gas, but only when placed in sunlight. It thus seems likely that these gases play some role in the process. Or, perhaps it is more correct to presume that light assumes some role in the integration of these substances. Where animals clearly incorporate eaten material into their growth, most plants instead appear to derive their mass from some combination of water and ‘bad air’11. Light might act as an ingredient for whatever process drives this. We are living in exciting times – the answers to many mysteries seem barely out of grasp, and to seize them we only need to extend our intellectual reach a little further.

Although the circumstances in which we are leaving are less than desirable, I now find myself filled with enthusiasm for the road ahead. My obligation as a missionary has now reached the end of its ten-year term, and a world of possibilities is opening before me. My uncomfortable time among the friendly heathens here, along with my decade of previous missions, has surely banked me some goodwill with the Order. I fully intend to cash it in.

I must return to Forum, as ordered, to report on the mission. But from there I wish to take on a project of my own, to which I have already alluded - if vaguely. There is a mystery I wish to solve. I will disclose more in my next entry; once more, the eternal autumnal light in which these woods are bathed is reddening. It is time to rest.

1 Although it has been argued that Proesus and Essichard are distinct continents, Essichard is far smaller, and they are at least physically joined - if barely. On the other hand, terming such a monstrous landmass a mere peninsula, as has been done in the past, seems even more preposterous. I prefer the term 'subcontinent' to describe Essichard, as recently proposed among those who study such things.

2 The villagers are knowledgeable enough to recognise mushrooms, lichens and other fungi as distinct from plants. I wonder how they came by this discovery – few are the societies that would make the distinction between plant and fungus before having seen both under a microscope. Even in the highest scientific circles of Proesus, the fields of botany and mycology have only diverged recently.

3 Were it a settlement of my own kind I surely would have. A year is one thing, but a Paluchard cannot live her entire life on meat alone without severe drawbacks to her health. I wonder how the people of Canopy fare – Nuntia cannot normally eat meat in any great quantity.

4 There is a blanket ban on any use of magic by the Order, as it is considered a corruption of Febregon’s power. However, a black market of magical artefacts thrives even in Forum, the seat of Order power. Taragos seems to feel himself above such rules; his reasoning makes use of the fact that the offending spell was cast not by him, but by another individual. I do not think this would hold up before an Inquisitorial Board, but I am not complaining. I doubt that I could have survived the year without making good use of his blasphemies and hypocrisies.

5 Even after a year of subsisting primarily on them, my stomach turns at the thought of their long-snouted little faces peering at me in judgment! More so at the undeniable truth that, in introducing the concept of agriculture to their captors, I am partially responsible for their plight.

6 I regretted performing this experiment immediately; although deadly only to small animals, the poisonous sting is very painful even to sapients.

7 While the stinging nettle and its malevolent ilk are contenders for this title, the chemicals they inject are never deadly except to those with severe allergies, and act only in self-defence.

8 Ecology is an emerging sub-field of the natural sciences, being the study of the tangled web of relationships between various living things and their physical environments. Just how complex these relations are is only just becoming apparent, and, I judge, remains severely underestimated. The formation of these relationships is what most fascinates me. Can such convoluted intricacies of symbiosis and predation, of interdependence and competition, have come into being all at once? How, without some manner of change or adaptation, can they withstand the extinction of one or more of their members - an event which there is little remaining doubt occurs with some regularity?

9 The erefal termite (Geoinuippyeoleul ssibda), is a prime clearer of detritus here. Although usually restricting itself to the dead wood of fallen trees and branches, it can sometimes be found tunnelling inside live erefal trees - a fact which places it among Leafshrine's most-hated animals. The villagers never pass up an opportunity to extinguish a colony of the insect, which I feel misses the valuable role they play in the interlocking systems at play here in the Wood. Never mind, for it is a losing battle - outside Leafshrine's small circle of influence, colonies of the termite can be found thriving with impunity.

10 Likely a more primitive relative of the leafcutting ants found in Veduka, whose agricultural practices are significantly more sophisticated.

11 Although plants certainly derive some nutrition from the soil, it cannot be their main source of nourishment, as demonstrated by experiments in which both soil and plant are weighed throughout the stages of growth. These experiments rely on the conservation of mass, a principle which alchemists have been toying with for some time but which has only gained serious traction with the other sciences in this century.